The slope of the US Treasury yield curve is one of the most widely watched economic and market indicators in the world.

However, as I’ve written before in this service, the yield curve is widely misused and misunderstood.

The most crucial point to understand is this:

Contrary to popular belief, an inverted yield curve – where short term yields are higher than long-term Treasury yields – is NOT an indicator of imminent recession.

At its heart, an inverted yield curve simply means the market sees Fed monetary policy as tight. That’s because the Fed has the most direct control over short-term interest rates – 3-month T-Bill yields and 2-Year Treasury yields are two common definitions of short-term rates. Meanwhile, market participants set long-term yields like the yield on 10-year based on the outlook for economic growth, inflation and rates over the long-term.

So, when the yield curve inverts – the yield on 3-month or 2-year Treasuries – rises above 10-year yields, it means that the Fed is pushing up short-term interest rates while the market expects economic growth, inflation and rates to fall over the longer term.

I’ve written about this phenomenon extensively including in the January 24th issue “Yield Curves, Recessions and Bear Markets,” and the June 22nd issue “About that Yield Curve,” so let me give you the executive summary today with two bullets:

In economic cycles since the 1970’s it’s not a yield curve inversion that signals imminent recession, it’s the re-steepening of the curve to a positive slope, which normally happens just a few weeks before the start of recession. The re-steepening generally occurs because the Fed starts to drive down short-term rates as the economy weakens, what’s known as a “bull steepening.”

In inflationary cycles such as the late 60’s and 1970’s, the Fed tended to keep monetary policy relatively tight even as the economy weakened to combat inflation. As a result, the yield curve tended to invert before the recession started and then remain inverted through most of the subsequent economic downturn.

Long story short:

The Yield Curve is Re-Steepening Right Now

Let’s look at the slope of the US Treasury Yield Curve right now.

I measure the slope of the curve in two ways – 10-year yields less 2-year yields (10s/2s) and 10-year Treasury yields less 3-Month Treasury Bill rates (10s/3M):

Source: Bloomberg

As you can see, the 10s/2s version of the yield curve (blue line) inverted briefly in April 2022 and has been consistently inverted since early July 2022. The 10s/3m version (orange line) has been consistently inverted since early November last year.

While it’s tough to believe right now following one of the most aggressive tightening cycles in decades, the Fed still had the Fed Funds rate pegged at zero until mid-March 2022 and the central bank was still conducting QE in the spring of 2022.

As the Fed began tightening, tentatively at first in spring and then more aggressively in the summer of 2022, short-term yields began to rise, inverting the yield curve. This is as you’d expect – as I outlined above, an inverted yield curve tells you nothing about the economy itself, only that the market views monetary policy as tight.

And, historically, there can be long lags between first yield curve inversion and the start of a recession. For example, the 10s/2s first inverted in December 2005 and was inverted continuously from the summer of 2006; yet, the US didn’t enter recession until December 2007.

Allow me to be blunt: Anyone telling you the yield curve is “broken” as an indicator because it inverted last year, and the US isn’t yet in recession, hasn’t done their homework.

What’s interesting is that we’re now getting that dreaded re-steepening.

The 10s/2s reached maximum inversion of -108 basis points on July 3, 2023 and now stands at just -18.6 basis points while the 10s/3M hit maximum inversion in early May at around -185 basis points and now sits closer to -50.

In cycles like 2000-02 and 2007-09, a good rule of thumb is that recession is imminent when the 10s/3M curve re-steepens to around +50 basis points after a significant period of inversion.

In 2001, that signal triggered in March, contemporaneous with the start of a mild recession in the same month. And in 2007 this signal flashed red in June; the market peaked in October and the economy slipped into recession in December 2007.

Obviously, we’re not quite there yet because the curve has yet to regain a positive slope, but the rapid re-steepening of both the 10s/2s and 10s/3M curves over the past few months is consistent with what we saw very late in the economic expansions ahead of the 2001 and 2007-09 recessions.

However, there are plenty of pundits claiming once again that the yield curve is broken and uttering some version of the notoriously expensive phrase “This time it’s different.” The main argument is the re-steepening event we’re seeing right now is different from those in 2001 and 2007-09.

Let me explain:

Bull Steepening vs. Bear Steepening

There are two main ways for the yield curve to steepen – either short term interest rates can fall faster than long-term rates or long-term rates can rise faster than short term rates.

The former is known as a bull steepening because when bond prices rally, yields fall. This is the type of yield curve steepening we saw ahead of the 2001 and 2007-09 recessions; the yield curve steepened because market participants began to anticipate imminent rate cuts, driving down short-term interest rates.

In both modern cycles inflation wasn’t a major issue – at least not anything close to the inflation problem we face today – so the Fed actually started cutting interest rates at the first signs of economic weakness to support the economy.

In 2001, for example, the Greenspan Fed cut rates 50 basis points in a surprise move on January 3rd and followed through with a second 50 basis point cut by the end of that month. And in 2007, the Bernanke Fed first cut rates in September; the anticipation of that cut, and further cuts in October and December 2007, are what drove the bull steepening in the yield curve in June 2007.

In contrast, the current market is experiencing a bear steepening. As I said, the 10s/3M curve has moved from an inversion of -185 basis points in early May to around -50 today. Since that time, the yield on 3-month T-Bills has actually risen around 27 basis points from 5.18 to 5.45%. All the yield curve steepening we’ve seen in 10s/3M since early May has been driven by the roughly 157 basis point jump in 10-year yields from 3.34% in early May to 4.91% today.

So, the argument goes something like this:

The yield curve “works” as an economic indicator because the Fed slashes rates as the economy enters recession, causing a bull steepening of the yield curve. In this case, the curve is bear steepening because the economy has proven more resilient than expected, so the yield curve is broken as an indicator.

Unfortunately, that idea isn’t supported by financial history.

As I mentioned earlier, in inflationary downcycles like 1973-1975, the yield curve remains inverted through most of the recession, because the Fed isn’t at liberty to cut rates to support growth with inflation elevated.

In effect, the two sides of the Fed’s mandate – low unemployment and inflation – are pulling in different directions during inflationary cycles. In contrast, in 2001 and 2007-09 inflation fell sharply headed into the downturn, allowing the Fed to focus all its attention on the growth/unemployment side of its mandate.

However, within bear cycles like 1973 to 1975 there are still steepening events:

Source: Bloomberg

This chart shows the slope of the 10s/3M yield curve from the end of 1971 through the end of 1975, a period which included the nasty recession and bear market cycle of 1973 to 1975.

The thick vertical lines represent the start and end of the recession per the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) Business Cycle Dating Committee.

As you can see, the yield curve first inverted in June 1973, about 5 months before the recession started in November 1973. As the cycle continued, the yield curve remained inverted most of the time until the autumn of 1974, roughly 5 to 6 months before the recession ended.

What’s interesting is that there were multiple steepening and flattening events through this cycle both before and after the start of the recession; I’ve labeled many of the major steepening events with black arrows.

What’s crucial is that much like the current environment many of these were bear steepening events.

For example 10s/3M was inverted to the tune of -185 basis points on November 13, 1973, and regained a small positive slope by February 5, 1974. The curve then bounced around a bit until July 25, 1974 when the curve regained a positive slope of 45 basis points.

So, on November 13, 1973, the 10-year Treasury offered a yield of 6.76%, rising to 7.75% on July 25, 1974, a jump of roughly 100 basis points. Over this time period, 3-month T-Bill yields were volatile ranging from lows near 6.90% in February 1974 to as high as 8.90% in April and May of the same year.

Recall, as I outlined earlier, that an inverted yield curve doesn’t actually mean imminent recession, it’s simply an indication the market sees monetary policy as tight. In 2001 and 2007-09, the curve regained a positive slope ahead of the economic downturn because the Fed loosened policy rates to combat weakening growth.

In 1973-75, the cycles of flattening and steepening indicated the central banks “stop-go” efforts to combat inflation; the ultimate end of inversion in late 1974 and early 1975 represented the Fed “giving up” the inflation fight as the recession deepened and unemployment soared to the highest levels since the 1930s Great Depression.

Note that several of the steepening events of this era were driven at least in part by rising 10-year yields – bear steepening.

So, the yield curve is “broken” as an indicator only for those with a recency bias, comparing the current situation to the low inflation era since the early 1980s. It’s not at all unusual in the context of a inflationary cycle like 1973-75 where the central bank has to balance price stability and unemployment/growth mandates.

And, as I’ve maintained for some time now, persistent inflation, rising commodity prices and uncertainty at the Federal Reserve regarding the need to further hike rates all suggest the inflationary cycles of the 1970s are a better guide for the current market environment than anything we’ve seen in the past 40 years.

My view remains that the “this time it’s different” crowd will ultimately be proven wrong, the US will enter recession and stocks will ultimately break below their late 2022 lows.

It’s Put Up or Shut Up for the Bulls

One last note.

In my Tuesday past “Market Breadth and Q4 Rallies,” I wrote that the S&P 500 was still clinging to key support, leaving a legitimate case open for a tactical seasonal rally into year-end.

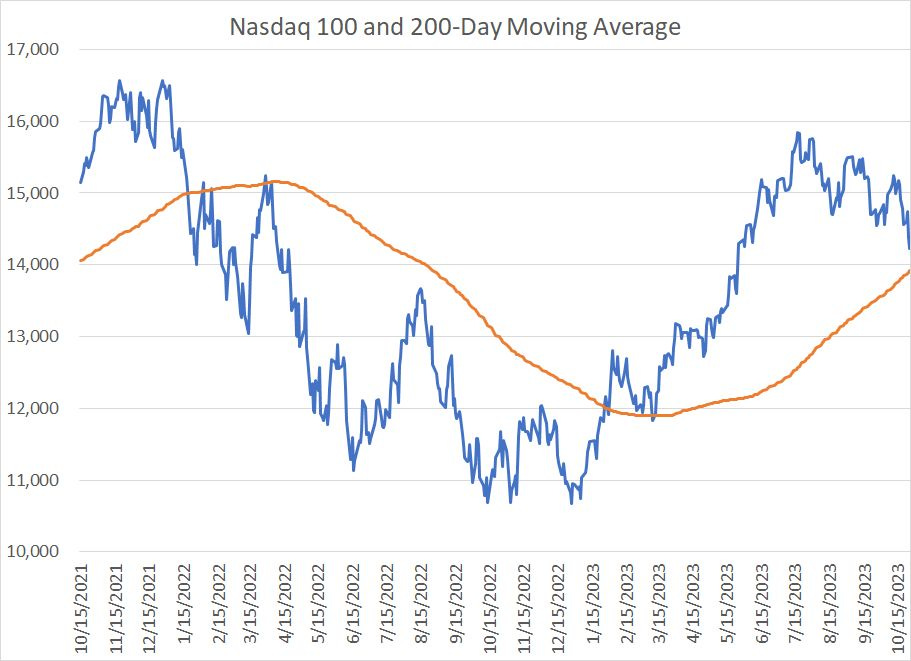

Since that time, the market has weakened further, led to the downside by the Nasdaq 100:

Source: Bloomberg

The Nasdaq 100 now looks to be headed for a retest of its own 200-day moving average following weak results from some of the Magnificent 7 this week.

With market leaders crumbling, and the S&P 500 trading more than 1.5% below its 200-day moving average, equity bulls are skating on very thin ice.

I’m still inclined to give the bulls the benefit of the doubt. However, if we don’t soon see some sort of strength around key support levels, and a recovery back over the 200-day moving average in the S&P 500, it will be time to take additional steps in the model portfolio likely involving inverse ETFs.

In contrast, I believe this week has marked at least a key short to intermediate-term low for longer-term Treasuries (peak in yields). In particular, I’d note the 10-year Treasury bond has pushed over 5% on a few occasions intraday, but has failed to sustain yields above that marker by the close of trading.

Further, two prominent bond bears – Bill Gross and Bill Ackman – recently turned more bullish on fixed income.

If you’re not yet a paid reader to FMS, I’m still offering 60-day free trials to the service via this link:

This offer closes Friday November 3rd.

DISCLAIMER: This article is not investment advice and represents the opinions of its author, Elliott Gue. The Free Market Speculator is NOT a securities broker/dealer or an investment advisor. You are responsible for your own investment decisions. All information contained in our newsletters and posts should be independently verified with the companies mentioned, and readers should always conduct their own research and due diligence and consider obtaining professional advice before making any investment decision.